Programmatically Irrational - To Code or Not To Code

02 April 2018

TweetPrologue

We developers love to write code. We go to conferences to learn about the latest techniques and frameworks. Then when we get home we can’t wait to apply what we’ve learned. There is no better feeling in the world than to push some new (working!) code to production and see it run to benefit other people. However, often before we start coding, our bosses - whom have just come back from a trade show - are asking us about buying the hot new product that all their friends have been talking about. According to the whitepaper and the online product demo, it does everything you’re looking to build plus more! These days the developers have a significant say in these decisions (We just get stickers instead of fancy dinners). s To code, or not to code, that is the question. As in most engineering decisions "It depends …" But before we evaluate, it’s important to understand the bias at work on both sides: the hidden costs of free software and hidden costs of paid software.

The Hidden Cost of Free Software

Let’s face it, Open Source Software (OSS) has won. The world is filled with high quality open source libraries for developers to use without having to pay license fees. I love open source. I contribute to open source projects at the Apache Software Foundation (ASF) and the way I do business would not be possible without it. One of the first things that drew me to open source was the fact that it was FREE! There was no reason for me to ask my manager for budget, I just had to make sure that it had a business-friendly license (Like Apache 2.0) and I was off. Free is a rather amazing price point that defies traditional economics. One of the studies from the book "Predictably Irrational" by Dan Ariely shows how dropping a products price relative to anothers can make incremental changes in consumer preferences … that is until one of them becomes free. Moving the price to free can cause a massive shift in the free products favor. But this all makes sense, right? Free means I can have as much as I want. And that’s where our free bias starts to cloud our judgment fellow developers. The problem is that even free has a cost.

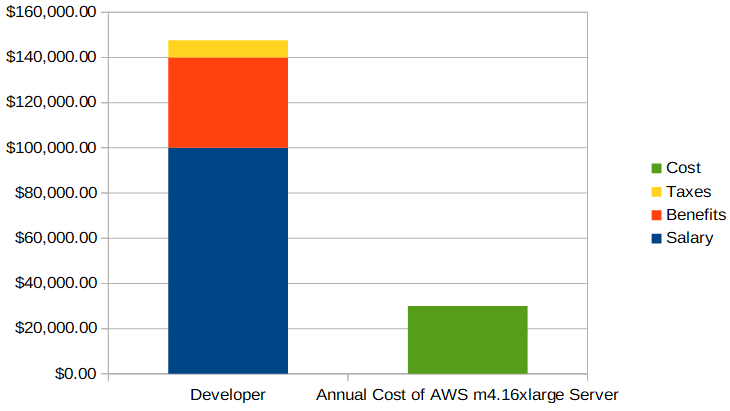

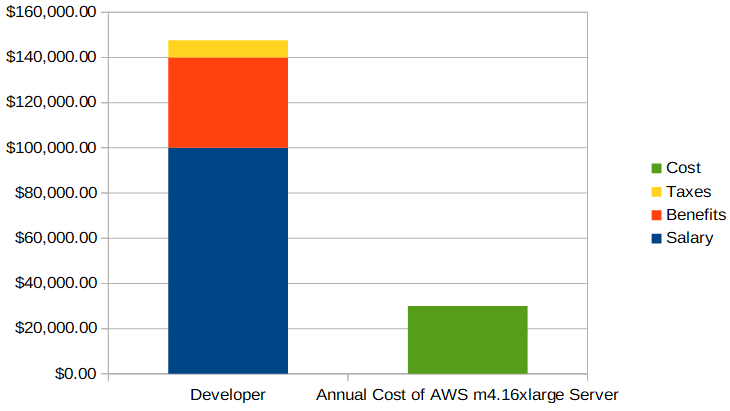

The most obvious cost is our time. While we’re building something new, is there something else we could be doing with our time to add value? This is called opportunity cost and often goes unnoticed until the end of the year. That’s when we realize we’ve been chasing shiny objects rather than working towards our goals. The cost of a developer’s time is generally the largest expense on a project. Compare the annual cost of a developer to a company compared to a large server. Bring that up the next time your boss wants to have an hour-long meeting to talk about infrastructure. The meeting probably could have paid for a month of hosting! But we’ll save that conversation for another day.

Deciding where we should be spending our time ends up being really important. To complicate this further we tend to overvalue the things we’ve spent our own time to build. This has been dubbed the IKEA Effect [1] and is discussed in another book by Dan Ariely "The Upside of Irrationality". The IKEA Effect can cause us to try to hold on to our own pet projects when better options are available (and cheaper). I can’t count the number of home grown responsive web frameworks and content management systems I’ve seen companies hold on to at the beckoning of the project’s long since promoted original developer. Folks, unless your company has found a way to monetize these systems, your pride is costing your company money. So much goes into creating and maintaining a piece of software. The cost of owning your product’s dependency tree is often under-estimated. That pang of fear you experience whenever you change a dependency version or switch to a new runtime comes from the fact that you realize that a simple change could be bringing in hundreds of lines of new code. This means taking some time to match up library versions to make sure the entire application is compatible. Platforms like JavaEE (now JakartaEE), Spring Boot and Apache Karaf try to lower some of these costs by providing tested library combinations that just work. The Java ecosystem is famous for its backwards compatibility. But it still may take some time to upgrade these platforms to newer versions.

Open source projects also vary on maturity and complexity. New or immature projects may require a little more work to get started. The ASF has a couple different ways to signal maturity. The first is the Incubator, which doesn’t always indicate that the code is not production worthy but does indicate that the project is new to the foundation and its processes/culture, aka The Apache Way [2]. This is important since time has shown that projects that adopt the Apache Way seem to have more staying power than ones that do not.

But even a project that has graduated has different levels of maturity. The Apache Maturity Model [3] might help you frame the conversation around adopting a new piece of OSS for your organization. Some OSS platforms are complex regardless of their maturity. Many of the Apache big data platforms (think Apache Hadoop, Apache Spark) and a number of new incubator projects (Apache OpenWhisk comes to mind) require significant distributed system experience to scale up and debug properly. So even though these projects offer incredibly cool functionality, most companies don’t have enough maturity in their engineering organizations to handle hosting this complexity. In that case it might be better to outsource the hosting to a specialist and just focus on the client code. Part of the power of open source is having the option to bring things in house if/when engineering matures and it becomes viable from a cost standpoint.

Finally, there’s the hidden cost of project abandonment. If the community around a project goes away, you might be left with security holes and old transitive dependencies making upgrades and maintenance difficult. Mitigating this risk requires spelunking a project’s mailing list or checking github for activity. Or perhaps even getting your company itself involved in the community! Some foundations like the Apache Software Foundation also have formal processes around monitoring project health so a project retiring to the attic is never a surprise. So even open source has costs and it’s important to weigh those costs before deciding to move forward with a project. Even free as in free beer has a cost, something I’m all too familiar with ;).

The Hidden Cost of Paid Software

Perhaps I’ve given you enough reason to at least hear your manager out on the product from the trade show. You might even like the idea that you can just take the cost of the software off a price sheet. It sure beats trying to estimate hours! But now that you’ve decided to pay for software, be it in the cloud subscription or an on premise license, is the only price the sticker price? Probably not. In the end it’s those additional costs that add zeros to the end of project costs.

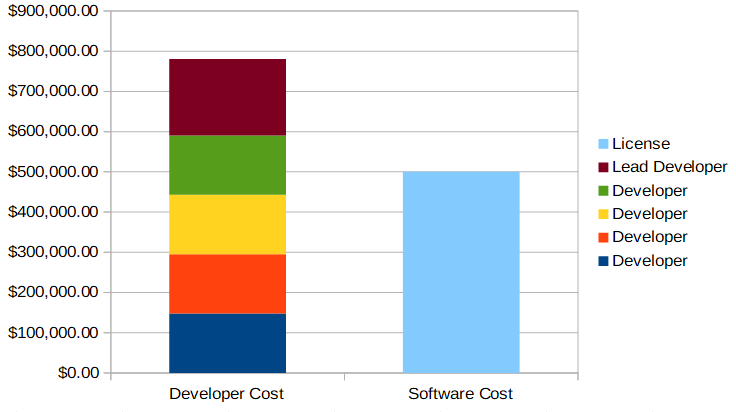

One of the most troubling criteria I have seen to evaluate proprietary software is ease of customization. Oh, you don’t like the way this works? Well you can go in there and write the code to change it. Developers feel right at home with this. But did we include the hours required to customize in the original build vs buy decision? Did we consider the cost of keeping those customizations when the product changes and evolves over time? If you did not you may be grossly underestimating the cost of the purchased software. Consider a $500,000 software license compared to the cost of a team of developers. Customizations will be the expensive part and we need to price that in. This favors the kind of software that works "Out of the Box".

In addition to that, the higher the investment cost, the more invested we get in making sure it meets expectations. This is known as the Sunken Cost Fallacy [4]. The more we invest in paid software, the more effort and customization we tend to put into it to make it work. This can create a vicious never-ending cycle of paying for software, ultimately resulting in bringing in expensive consultants to make it work. Then when the expensive consultants screw it up, we bring in more expensive consultants to fix it (I may have played that game before). In the end it’s important to decouple your already paid investment from the expected benefits at each phase of the project. This is easier said than done since it requires us to be able to swallow our pride and admit defeat from time to time. But isn’t not delivering a product that wastes $100k better than delivering a product that is DOA that wastes $1M? I think so.

Expertise can be hard to find as well, which delays implementations for months while waiting for folks to roll off projects. Once again, Opportunity Cost! One creative way companies have dealt with this is by open sourcing a community version of the product but keeping the tooling and operational aspects of the product closed. This way at least you can often produce a working POC prior to deciding to pay for the software. Then when things start to scale up the sales person gets a call. Scaling, however, can also lead to unpredictable costs based on how you’re paying for the software. Is it by cpu core, machine, per request? Hold on while I pull out my crystal ball! These can also manufacture engineering problems that you might not have with open source. For example, let’s say you only paid for 10 cpu cores for the database, but you spend hundreds of development hours optimizing queries. Or paying per request in the cloud made sense, until that DDOS attack didn’t just cost you sales, it increased your bill to Amazon.

Another hidden cost to organizations that rely heavily on purchased software is what I call engineering atrophy. Atrophy is what happens to muscles when you stop using them. They get weak and flabby. The same can happen to a company’s engineering teams if vendors are doing all the heavy lifting. This can get to the point where all the engineering teams are just placing support tickets or getting trained on the vendor’s next product. Good engineers want to be solving hard problems. The engineers that stick around to manage vendor relationships are generally ill-equipped to handle the challenge of a migration or bringing software back in-house. I’m not saying you need to build everything, but if all you’re doing is buying, it will catch up to you. Make sure to set aside challenging projects for your teams that add value to your core business. If you don’t keep working those engineering muscles, you are setting yourself up to be bullied by your vendors.

Lastly, when we buy a product we have to give up some control. You want to keep your indemnification? Better patch on the product schedule. Want to be on the latest Java version? Gotta wait for it to be certified or added to your serverless cloud offering. Need system level logs for debugging? Send a ticket … we’ll get to it eventually. When things are running smoothly these risks often go ignored. In fact, when a product or solution fits the problem, "Out of the Box" purchasing can be a great choice as many of these problems I’m calling out do not exist. However, without carefully considering the hidden costs, your team’s budget may be allocated for the next 5 years.

I think it’s fair to say as a developer that we’re not paid to code. We’re paid to solve problems that add value to the businesses that support us. That’s what keeps the money flowing to our bank accounts! It’s important to consider all the costs going into our build and buy decisions whether we’re going with open source or with paid solutions. Whether you’re returning from a conference or chatting with your trade show loving boss, remember: There’s no such thing as free lunch!